We’re going to follow up with our dive into file systems in the last issue with a look at another very important component of Linux–the windowing system. This component is what controls graphical environments–like your favorite desktop environment or window manager–to hook into an agreed upon protocol to implement their functionalities. Though there have been many ideas for newer display server protocols, it has become practically unanimous among the different Linux developers that Wayland is the way forward.

Let’s take a quick look at the history of windowing systems on Linux, why Wayland is an important milestone, and what the future may look like for the new(er) Linux windowing system.

Wayland History

In 1992, one of the most important events in Linux history took place–the porting of the X Windowing System (X11) to the Linux kernel by Orest Zborowski, which allowed graphical user interface (GUI) support for the very first time in the young, open source operating system kernel. However, X11 was not a new piece of software by any means at that time, in fact, it had already enjoyed nearly 8 years of development from it’s initial conception at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for a replacement to the W Windowing System, which was popular for Unix operating systems of the time.

Over the formative years of kernel development, X11 became integral to the Linux experience and, in 2004, the X.Org Foundation was created to ensure the continued development of X11. However, as Linux and its software ecosystem began to rapidly evolve, along with the exponential growth of differing chipsets and device forms (like Tablets and Smartphones), it was starting to become obvious that something was needed to replace the legacy architecture of X11 in order to keep Linux working across multiple devices and architectures. It wouldn’t take long before a formidable replacement would make its way into the greater Linux developer consciousness.

In 2008, a Red Hat employee and X.Org developer, Kristian Høgsberg, began working on a side project in his spare time. The idea included a very ambitious goal: create a new windowing system where “every frame is perfect, by which applications will be able to control the rendering enough that we’ll never see tearing, lag, redrawing or flicker.“. While traveling through the town of Wayland, Massachusetts, the architecture and implementation for Høgsberg’s project was finalized in the developer’s mind. With the major eureka moment, the project would take on the name of that small Massachusetts town, Wayland–in honor of Høgsberg’s breakthrough there.

By October 2010, Wayland was accepted as a supported project by the freedesktop.org initiative. In response, many in the Linux developer community declared Wayland as the future of Linux display and the successor to X11. A collection of the X.org developers began working on Wayland as well as a compatibility library, XWayland, in order to smooth the eventual transition.

By 2013, almost everyone had declared their support of Wayland. However, Canonical, the creators of the most popular desktop Linux offering in the world, Ubuntu, were not satisfied with the progress that had been made on the Wayland display server as well as the current functionality available. With an upcoming push towards mobile convergence with the new Ubuntu Touch mobile operating system and Ubuntu Edge mobile phone, Canonical chose to announce a different project, Mir, that directly competed with Wayland, in order to move up the timeline for Ubuntu Touch (and its Unity8 interface).

Of course, this decision was extremely controversial in the open source community and many complained that Canonical was splitting off valuable engineering resources from Wayland. Both projects were worked on for five years until Canonical announced the discontinuation of their convergence initiatives as well as the Unity desktop environment, which would be replaced by GNOME 3 in the 18.04 LTS release. Because Wayland and Mir had diverged considerably over the years, Canonical announced that development of Mir as a Wayland competitor would be halted. Instead, the code was open-sourced and the Mir developers chose to pivot the project into a Wayland compositor. Today, all sights are set on Wayland once more–allowing for a united development front to the project.

The Wayland Architecture

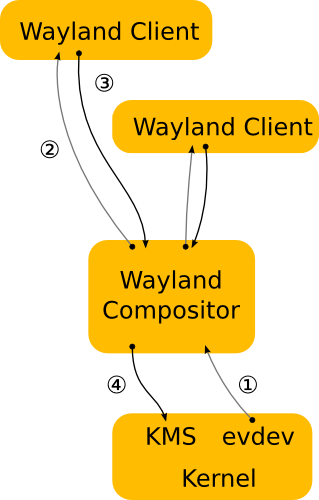

It is important to remember that Wayland is simply a communication protocol that allows a display server to talk to its clients. The Wayland protocol is implemented as a C library for easy interaction with the Linux kernel and its different components. In the Wayland model, a display server uses the Wayland protocol to interact with clients and, in doing so, becomes a Wayland compositor. The Wayland compositor is what does a lot of the heavy lifting like merging the window buffers into an image representing the screen as well as blending, fading, scaling, rotating, or duplicating the applications present on said screen.

Since Wayland is simply the protocol, compositors must be built using the Wayland protocol–a job that has been taken on by downstream Linux desktop environments. The Wayland developers have put out a reference implementation, known as Weston, to try to ease the burden as much as possible. However, Weston is just that–a reference implementation that should NOT be used in production.

The Wayland implementation consists of a much simpler architecture. Unlike the X11’s structure, a Wayland compositor is the display server. The control of KMS and evdev are transferred directly from the kernel to the compositor. Therefore, the Wayland protocol allows the compositor to send input events directly to the clients and lets the client send any damage events directly back to the compositor.

This allows the system to bypass many of the procedures that are required for X11 communication between the X server and X compositor, removing latency at each level of the transactions. Of course, because Wayland isn’t considered “prime time” just yet, a migration path has been made between X11 and Wayland, aptly named XWayland, which is especially good for those that rely on backwards compatibility. This architecture adds back in the X server, which connects to the Wayland compositor and serves X clients that do not speak the protocol.

The Way Forward with Wayland

Though work on Wayland has been ongoing for nearly a decade, it is still unable to be used as the standalone display server without XWayland in the mix. Therefore, adoption of Wayland by many distributions has been few and far between. Moreover, because of NVIDIA’s refusal to open-source their drivers and focus on Wayland, many people would simply be unable to use the display server if they have an NVIDIA graphics card. Considering that this is quite a large portion of the overall PC market, making Wayland (or even XWayland) the default is not recommended.

However, several desktop environments have been hard at work building their own compositors for the Wayland protocol, with GNOME and KDE leading the pack. Today, it seems that every major release brings both one (or even multiple) steps closer to being able to use Wayland by default. Due to this increased support and compatibility, GNOME allows for a Wayland session to be chosen during login in place of X11. In fact, in 2016, GNOME’s display manager (GDM) changed the default session to Wayland (with XWayland) over X11. However, most distributions change this behavior from upstream GNOME to keep X11 as the default windowing system.

One distribution that doesn’t is the Red Hat community’s Fedora distribution, which is known for keeping its implementation of GNOME 3 as close to the upstream as possible, including using Wayland by default. This makes sense, as many of the X.Org developers that work on Wayland as well as core GNOME team members are also Red Hat engineers and both have had ties to the company since very early on.

Fedora has long been a testing ground for features and components that may eventually make their way into Red Hat’s enterprise offering, Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL). Because of it’s progressive use of cutting-edge features, Fedora has become one of the most popular distributions, especially among developers that work on core systems-level components in the Linux ecosystem.

So, as Wayland continues to improve and compositors using the protocol become more refined, we should see adoption of Wayland happen over the next few years. I know that I’ll be keeping an eye on the progress that the Wayland developers make!

This article is an excerpt from Issue 24 of Linux++

You can read the full issue by going here.

I know this article is a while ago, but here is a minor correction nonetheless.

The statement:

“Instead, the code was open-sourced and the Mir developers chose to pivot the project into a Wayland compositor.”

can seem to imply that Mir was not Open Source until its pivot.

This is simply false, as it was GPL from the much earlier beginning. This is quite apparent from a read of the Wikipedia page about Mir and its references, such as this one:

Oh yes, if Ubuntu had beaten Pine phone and produced the first Linux phone how different the Linux market could look now.

The phone could have been a great success, Mir for the desktop would still be under active development. Wayland and Mir would have been actively competing against each other on the desktop. And Ubuntu would still be active in pushing their Distro of choice to be cutting-edge.

laughs in BQ Aquaris

I was almost half serious…

But you have shattered the moment now.

Fine, looks like my next phone is a Pine phone.

Join the discussion at forum.tuxdigital.com